Glass Beach is visual proof that beauty can be generated from the unlikeliest of sources. The Fort Bragg, California beach is the result of early twentieth century residents dumping their garbage over the cliffs. The refuse included glass (of course), appliances, and even automobiles. Periodically, beach patrons and authorities would light fires to reduce the amount of garbage on the beach. Over the decades waves pounded the shores and broke down everything but the glass and pottery. What was left was worn into the smooth and colorful glass and stone that cover Glass Beach.

Hello Everyone, I have 8 years experience in various fields like commercial, documents and quality in one of leading multinational company. Here from this platform i will try my best to share some knowledge which will never you can learn from any school, college or university. I was overwhelmed when i see various tools, soft wares, techniques and concepts that make daily working very smooth and efficient and I also believe in that "Sharing is caring". So I hope you will enjoy my posts. Thanks.

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Sunday, May 25, 2014

IT security governance: Boards must act

IT security governance: Boards must act

Summary: Implementing an

effective information security governance framework with the right leadership

structure is not an easy task, but failing to do so could mean the difference

between a contained crisis and a devastating catastrophe when things go wrong.

Businesses live with risk. Risk

is an opportunity and a threat that business leaders regularly assess to

determine what they can live with and what they feel they must mitigate. But

while some risks and their impacts are well understood, information security

risks — and the severity and suddenness of their impact — remain tough to

conceptualise for many. Business leaders often only understand the true scale

of information security risk when a major incident spells it out — with

unimagined consequences.

US retailer Target might be the

(reluctant) poster child for a security breach at the moment, but it's not

alone. Organisations face and can suffer from a diversity of security risks and

impacts: Cybercriminals, insider threats, "hacktivists", denial-of-service

attacks, and even offensive foreign government acts.

Do boards really understand the IT security risks for their

organisation?

A telling question about the

security governance framework in place at any organisation that's suffered a

major breach is whether the board discussed cyber security before the incident.

Did it understand the risk, the probability of its occurrence, and its impact?

If it was surprised by the incident, chances are the risks and their impact

weren't discussed.

Information security governance

isn't about the technical aspects of IT security. It's about defining

responsibility and accountability, and structuring policies to ensure that

decisions are made in such a way that they help an organisation achieve an accepted

level of risk.

The US National Institute of

Standards and Technology (PDF) defines it for US government departments as

"the process of establishing and maintaining a framework and supporting

management structure and processes to provide assurance that information

security strategies are aligned with and support business objectives".

The framework would also ensure

that such strategies are "consistent with applicable laws and regulations

through adherence to policies and internal controls, and provide assignment of

responsibility".

Designing and implementing an

information security governance framework will help manage risk, but it could

also jar with an organisation's culture, particularly when it comes to who's

calling the shots.

For example, should the chief

information security officer (CISO) have a direct line to the board or CEO? Or

perhaps the power to veto a business project that involves an unacceptable

security risk? Or should the CISO do everything possible to align security

objectives with business goals, perhaps to the detriment of sound IT security

risk management?

Are suppliers and contractors to

be included in the governance framework? Is there a role for cyber security

insurance in offsetting risk — and at what expense? And how should

organisations define where the information risks lie? Is it just in vulnerable

IT systems? Or paper, too?

Governance structure is going to

be critical to the overall framework, and one common sign that a board of

directors probably doesn't have a grip on the information risks it faces is

when information security leadership is tucked away behind the general rubric

of IT.

Who should the CISO report to?

"The CISO should not report

to the CIO," said Jeff Spivey, international vice president of the Information

Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA). "It's very difficult to

bring up issues to a management level that needs to resolve them. That needs to

be offset somewhere else so it's not an incestuous relationship."

Jeff Spivey, international vice

president, ISACA

David Lacy, a UK-based strategic

advisor to security firm IO Active and the original author of the British

Security Standard BS7799 — a predecessor to today's ISO 27000 series of cyber

security standards — agrees. He added that putting the CISO on a leash leaves

an organisation poorly prepared to deal with the blistering speed of today's

attackers.

"In today's environment,

major security vulnerabilities need to be fixed immediately. CISOs should be

trusted to make the call. There's no time to argue or make a business case. And

very few security business cases meet investment appraisal criteria," said

Lacy. If that means the majority are declined, surely the board and

shareholders have a right to know?

Lacy, previously an information

security manager for Royal Mail Group, Royal Dutch-Shell Group, and the UK

Foreign & Commonwealth Office, believes traditional security governance —

and the standards used to build them — need to be abandoned. Instead of

security leaders thinking like widget makers, they need to act with a fighter

pilot's sense of peril.

"Cyber security increasingly

needs to operate like a strategic crisis team. In a crisis, a team takes over

decision making from the business. Speed and empowerment are crucial."

The problem, according to Lacy,

is that security leaders are often too afraid of losing their jobs to stick

their necks out when it's needed.

"There's always resistance

to security because it costs money and slows down projects. The main risk to a

business manager is always his bonus. It's never security. CISOs won't stand up

to the business because they want a career. That's the reason we have

compliance. But compliance does not result in effective security." Maybe

business managers' bonus objectives should include a security measure?

How does an information

governance policy work?

Policy documents aren't the most

thrilling reading material, and are often not treated with the importance they

deserve — sometimes because they've been poorly fitted to the organisation.

However, in complex and dynamic environments with multiple stakeholders,

well-defined policies can be critical to managing information risks as

decisions are made.

The trick to ensuring that

policies don't get ignored is to avoid seeing them as an audit checklist, which

of course requires effort that some companies aren't prepared to expend.

"Too often, I see companies

use policy templates downloaded from the internet, or the policies do not

reflect how the business operates," said Brian Honan, principal of UK

security consulting firm BH Consulting.

"This results in policies

being ignored by staff and management, and the policies left to gather dust on

a shelf somewhere. Their only function is to satisfy an audit requirement,

which even then they may not achieve."

Honan added that they should be

treated as "living documents" that are updated regularly and easy to

access.

Well-designed risk management

policies offer a base from which to take a calculated approach to information

risks that will also shine the light on opportunities.

"It is quite ironic that

security professionals often discuss risks without considering the

opportunities," said Dr Steve Purser, who heads up the technical

department of the European Union's official security think tank, the European

Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA).

"Most of us do not take

risks unless there is a clear reason for doing so, so it's important to

understand the business motivation for doing something when considering the

risk. In other words, a good risk management framework will enable the

management to take account of both opportunity and risk."

Once they've been worked out, the

organisation is able to inspect what risks can be mitigated and those that

remain.

It's also a fall back document

for when business managers overstep the limits of their decision-making powers.

It ultimately clarifies where accountability for decisions lies, and ideally

removes assumptions and ambiguity about who has the authority to make them.

"When these limits are

reached, the governance policy explains the mechanisms and procedures that must

be followed in order to control the risks in an appropriate fashion,"

explained Dr Purser.

Besides keeping the organisation

clear of wayward decisions, the policies can also help shape cultural attitudes

toward risk and security, which may ultimately improve the response to a

security incident when one, occurs.

"Used correctly, they can

also be useful tools in educating staff on what the organisation regards as

being a reasonable level of risk and what is intolerable, which in turn helps

organisations to be prepared for security incidents and other unusual

events."

Building and implementing the right policy and framework

Building an information security

governance framework is all about understanding the business, the unique risks

each unit faces, and working with each to achieve an optimal risk profile.

However, it's also a balancing

act between different priorities, since risks seen through the eyes of an IT

security professional will be different to a business executive's. Neither

should be overruled without consideration for the overall organisation.

Ultimately, building the

framework will require input and support from every level of the organisation,

from the board to those executing the policy on a daily basis.

"A common issue with

implementing information security governance is failure to get the buy-in of

those that have to implement the framework," said ENISA's Dr Purser.

At a practical level, Honan

pointed out, this means engaging business, to ensure that the policies align

with their goals, and end-user representatives, to ensure that they're

understood by those who will use them.

"The language used in the

policies should be simple and straightforward, and it may be worthwhile having

someone act as a 'policy translator' to ensure the language used is

appropriate," advised Honan.

This type of engagement will also

help refine where the organisation invests in security.

One example, said ISACA's Spivey,

is where a unit knows that the impact of a disruption or outage to a particular

system would knockout manufacturing for a day with a cost of $3 million.

"The cybersecurity group

tells me what it takes to lower that risk for my business unit. It's a

discussion about where's the value in each business unit, and how can those

units be affected by these risks that cybersecurity group sees. Impact is

important," he said.

"A lot of times in IT

security, we think our risks are the most significant risks for the entire

company," said Spivey. "The enterprise risk management

responsibilities have to first understand what those risks are from a

cybersecurity point, and then weigh the impact of those risks to other risks

the company faces. And then apply the resources to ensure that risk is within

[what] the board agrees is acceptable."

Governance structures at a

leadership level may also require organisations to take an information-centric

view of security. Spivey pointed to the emergence in banks of "information

risk officers".

"My argument would be that

person needs to be involved in information, no matter where it resides. It

could be on paper, data in a computer, public speeches. It could be a number of

different ways that information may not be controlled, limited, and protected

as an enterprise secret," said Spivey.

Standards and compliance: Pitfall or helper?

Information security standards

can help guide the process, and legal and regulatory compliance may kick-start

a program. However, they definitely shouldn't be the cornerstone to an

information security governance framework.

Some commonly referenced

standards include ISO 27001 and 27002, ITIL, ISACA's COBIT 5 framework, and

others such as the card scheme-backed PCI DSS. Then there are regulations

impacting information handling in certain sectors, such as HIPAA for US healthcare,

and more generally applied regulations like Sarbanes Oxley that place

obligations on US businesses and their overseas entities.

While each standard attracts its

own critics, they're not bibles. They can be used as a solid starting point to

implement a good security framework, said Mark Jones, principal of

Australia-based Enex Test Labs' security testing division.

Mark Jones, principal, Enex Test

Labs

"All the standards form a

baseline, but for nothing else [than] they give someone that's trying to implement

governance something to work towards, otherwise you'd be winging it and you'd

probably miss something," said Jones, pointing out that most organisations

do base their governance frameworks on one of them.

Standards and compliance may help

to establish baseline security measures and could be a vital part of a

governance framework; however, the organisation shouldn't implement a standard

with a view only to passing an audit. That approach is a mistake, according to

ENISA's Dr Purser, who said it could lead to a mess of security controls that

aren't fitted to the organisation's needs.

"Compliance-based approaches

can quickly become liability control mechanisms, and can lead the organisation

into a false sense of security. It takes a lot of consistent effort to

implement effective security controls, and even more effort to make sure that

they remain current," said Purser.

Posted by : Javedkhan Malek

Source from : www.zdnet.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

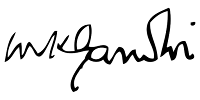

The Great Man and Signature in India - Vol 1

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Subhas Chandra Bose Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Jawaharlal...

-

VANOD STATE H.H. Inayat Khanji Kamaluddin Khanji Malik Born on 24th September 1956 in this princely state of Vanod, completed ...

-

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Subhas Chandra Bose Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Jawaharlal...

-

Cell phones have revolutionized communication in the 21st century, and their use has seen a rapid increase in recent years. As of Januar...